johndoe@gmail.com

Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be logged out in

Do you wish to stay logged in?

Please note that you will need to be logged in to view the content featured below

Since the 1970s Brazil has been one of the few countries in the world where the consumption of Brazilian music has exceeded that of music from overseas. Maintaining a constant international presence through bossa nova and trends in música popular brasileira, Brazilian music has been increasingly recognized by both musicians and scholars as having a constitutive role in the musical landscape of the world.

With this collection of freely accessible chapters, we explore the history and significance of Brazilian music throughout the 20th century.

From the mid-20th century to the present, the Brazilian art, literature, and music scenes have been witness to a wealth of creative approaches involving sound. This is the backdrop for Making It Heard: A History of Brazilian Sound Art, a volume that offers an overview of local artists working with performance, experimental vinyl production, sound installation, sculpture, mail art, field recording, and sound mapping. In a chapter by Tânia Mello Neiva, the author discusses the work of selected Brazilian women artists who are very active in the music and sound art scenes, and explores how they have been impelled—through their art and associated creative methodology—to question or try to break with some of the norms that symbolize and reproduce patriarchal and hegemonic values in the fields of experimental music and sound art.

Explore further by reading Tânia Mello Neiva’s chapter “Engaged Sonorities: Politics and Gender in the Work of Vanessa De Michelis" from Making It Heard: A History of Brazilian Sound Art.

What better way to affirm the out-and-out Brazilian-ness of one’s new album than to begin by employing the country’s most representative musical genre in a rousing rendition with lyrics about the most typical dish of the national cuisine? The opening salvo of the first Chico Buarque is one such affirmation: “Feijoada complete” (Complete bean stew meal) serves up on a sound platter an all-embracing black-bean stew repast, with all the trimmings and side dishes. This A1 track is characteristic of the encompassing collection with its sonic frame, crafted lyrics, elements of popular culture, and connections to other genres and dates. Throughout Chico Buarque’s First Chico Buarque, an entry in the growing 33 1/3 Brazil series, author Charles A. Perrone situates the album in inter-related contexts: the artist's own career; the evolution of Brazilian Popular Music; and, especially, historical conjuncture—his work spanning the period of military dictatorship in Brazil, 1964-85.

Explore further by reading the chapter “Setting the Table, on the Ground” from Chico Buarque’s First Chico Buarque by Charles A. Perrone.

Música caipira is a term used to denote the large group of musical subgenres performed in the rural areas of the “Middle-South” of Brazil—that is, the states of São Paulo, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul, Paraná, and the southern areas of Minas Gerais and Goiás. In the 21st century, música caipira is regarded as a basis of Brazilian popular music, one of its most traditional genres. It can be heard in many places in the Middle-South, chiefly at community events such as parties or on specialist radio programs. This genre is at the heart of debate about the transformations that urbanization and modernization have wrought in Brazilian society and Brazilian popular music. For many musicians and critics, the process of modernization that música caipira underwent, and the emergence of música sertaneja, are seen through a negative lens—one that laments the dissolution of many traditions. From this viewpoint, música caipira is a good index of the problems created by the modernization of society. Yet in spite of this, música caipira remains a powerful symbol of Brazilian musical and cultural traditions, in particular those of the Middle-South.

Explore further by reading Allan de Paula Oliveira’s chapter “Música Caipira” from the Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Volume IX: Genres: Caribbean and Latin America.

Most die-hard Brazilian music fans would argue that Getz/Gilberto, the iconic 1964 album featuring "The Girl from Ipanema," is not the best bossa nova record. Yet we've all heard "The Girl from Ipanema" as background music in a thousand anodyne settings, from cocktail parties to telephone hold music. So how did Getz/Gilberto become the Brazilian album known around the world, crossing generational and demographic divides?

Bryan McCann traces the history and making of Getz/Gilberto as a musical collaboration between leading figure of bossa nova João Gilberto and Philadelphia-born and New York-raised cool jazz artist Stan Getz. McCann also reveals the contributions of the less-understood participants (Astrud Gilberto's unrehearsed, English-language vocals; Creed Taylor's immaculate production; Olga Albizu's arresting, abstract-expressionist cover art) to show how a perfect balance of talents led to not just a great album, but a global pop sensation. And he explains how Getz/Gilberto emerged from the context of Bossa Nova Rio de Janeiro, the brief period when the subtle harmonies and aching melodies of bossa nova seemed to distil the spirit of a modernizing, sensuous city

Explore further by reading the chapter “Bossa, Race, and Politics” from João Gilberto and Stan Getz's Getz/Gilberto by Bryan McCann.

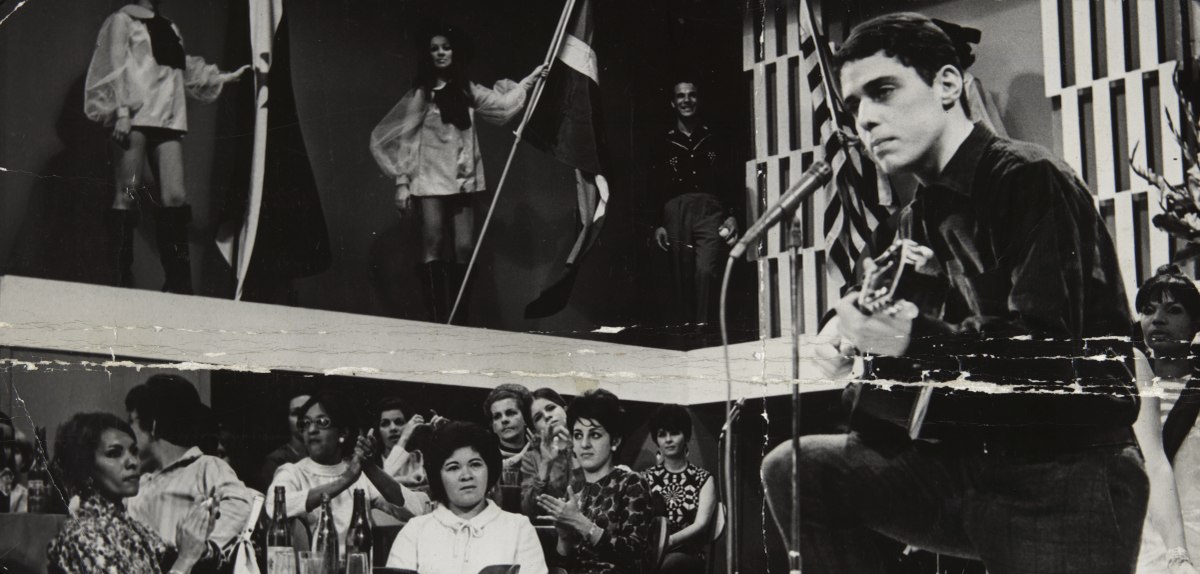

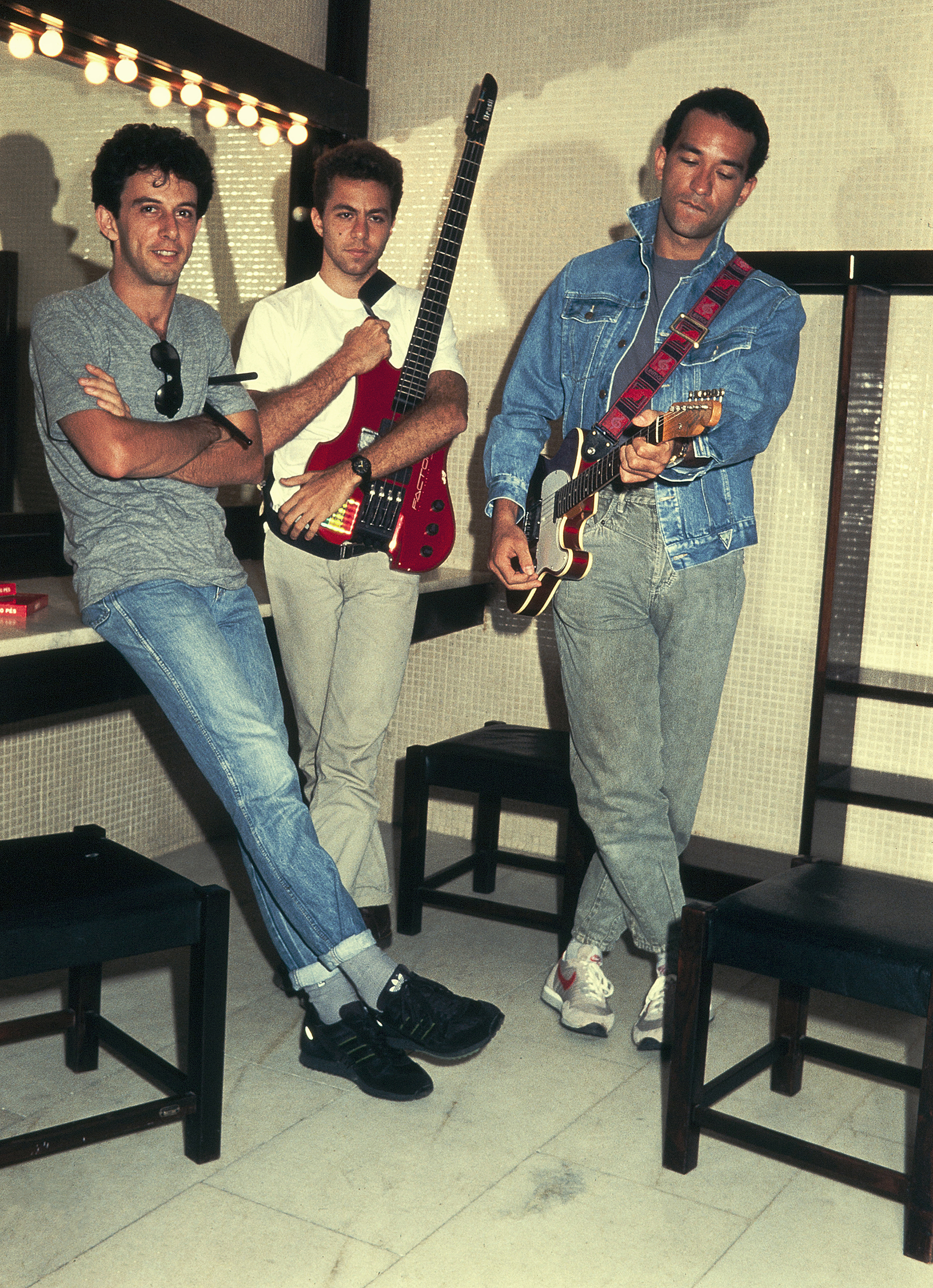

Rock performed by Brazilians dates back to Nora Ney’s 1955 cover of “Rock around the Clock” and Celly Campelo’s 1959 “Estúpido Cupido,” a translation of “Stupid Cupid” presented on the national television show Chacrinha. Brazilian rock, however, began in the early 1960s with a generation of singers influenced by the likes of Elvis Presley, Little Richard, and the Beatles, who popularized a distinctly Brazilian sound. Previously the domain of música popular brasileira, the flag of social protest was hoisted by many rockers. Bands in the 1970s under the dictatorship had their songs censored, and artists were tortured and exiled. It wasn’t until the 1980s that major labels such as CBS, EMI Som Livre, and Warner started to take Brazilian rock seriously. Rio’s Barão Vermelho, São Paulo’s Titãs, and Brasília’s Paralamas do Sucesso and Legião Urbana had gold and platinum disks and, with FM stations like Rádio Fluminense, Rádio Rock, and Transamérica behind them, silenced the decades-old epithets of rockers as alienated, Americanized, and colonized.

Explore further by reading Jesse Wheeler’s chapter "Rock Brasileiro (Brazilian Rock) from Encyclopedia of Latin American Popular Music.

As well as recorded music in various formats and across multiple platforms, live music is central to the musical experiences of many people. For audiences, the live music experience can be linked to fan commitment, feelings of communality, identity construction and cultural exploration. For musicians, performing live, alongside potential economic benefits, provides opportunities to engage with audiences and build a fanbase, demonstrate and develop musicality, and foster perceptions of authenticity. Since the hiatus imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the live music industry has in some ways resurged, with the record-breaking revenue from Taylor Swift’s The Eras Tour epitomising the appeal of the superstar arena concert. On the other hand, at a grassroots level, the live music industry is struggling, with small venue closures and cancellations of festivals, at least in the UK. Connecting with audiences and creating a sense of intimacy in live music performances, especially at large scale and online events, is a challenge, but the issues arising from the live music industry extend well beyond this. From the fragile ecosystem of the industry to sexual misconduct at live music events, as well as its environmental impact, the live music industry faces many challenges and is a fascinating and important area of research and activism.

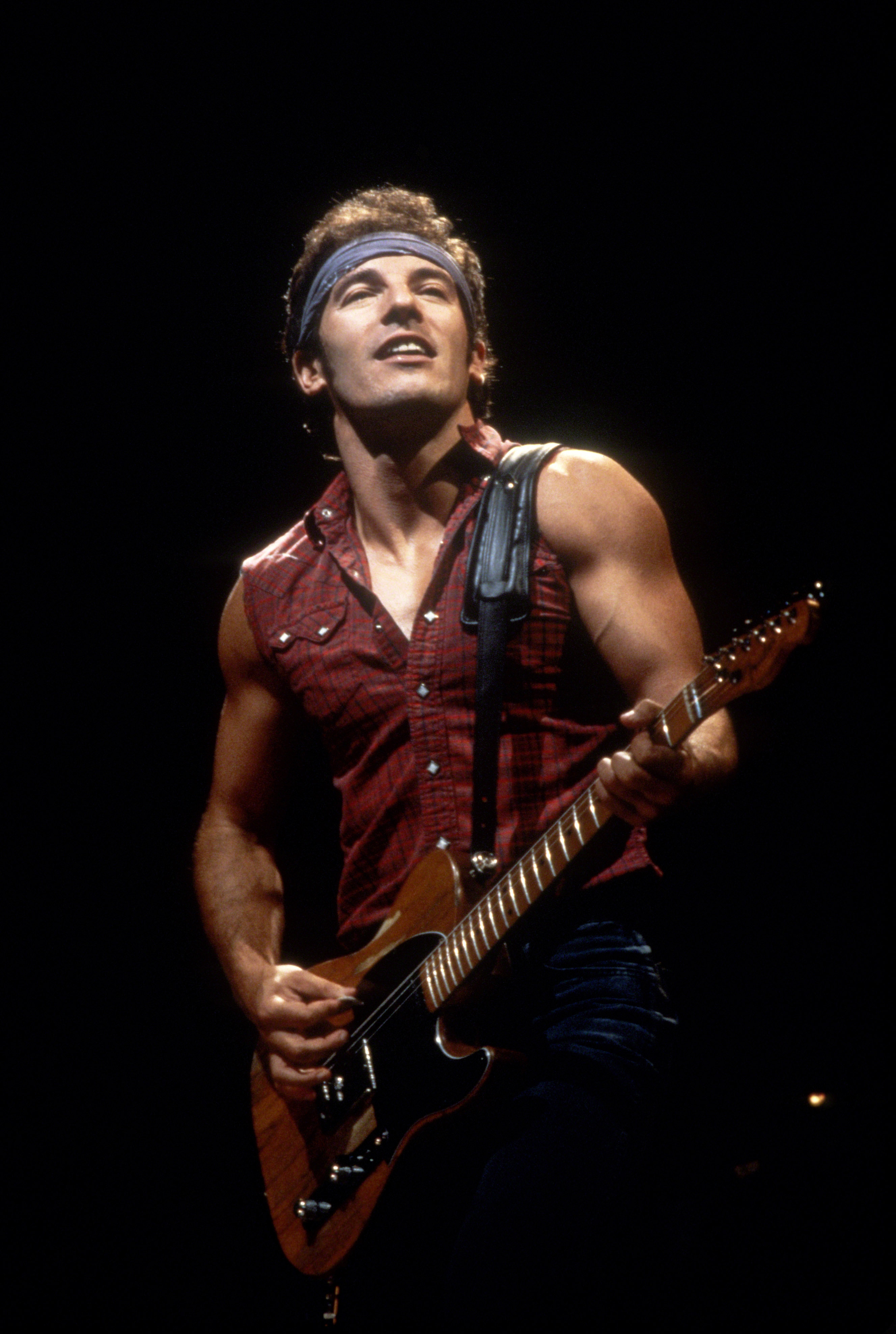

As a mass-produced commodity, it is perhaps surprising that popular music elicits feelings of intimacy with and among audiences. Musical Intimacy explores how intimacy is constructed and perceived in both recorded and live music. Live music is, of course, experienced in a range of contexts. Small spaces can create a feeling of intimacy simply through proximity of audience to artist, while large-scale events rely more on the relationship of the audience with the persona of the performer to create intimacy. Bruce Springsteen, for example, connects with tens of thousands of people in stadium concerts through his legendary ‘everyman’ persona. When the Covid-19 pandemic brought in-person live music to a temporary halt, live music performance flourished on online streaming platforms, with intimacy created through various means, including domestic-seeming spaces and situations, comment and live chat features, and ‘stitched performance’, such as the 2020 fund-raising effort One World: Together at Home, that technologically brought together remote performers, including members of the Rolling Stones, into a unified broadcast. Overall, although constructed, the intimacy that arises in live performance is ideally perceived as authentic. Springsteen in particular is a performer who audiences find to be authentic, in his music and in his physical presence. The argument put forth by Stiegler and Campbell is that audiences seek authenticity both in their experiences of live performance and in their experiences of intimacy.

Explore further by reading Zack Stiegler and Todd Campbell’s chapter ‘Intimacy and live performance’ in Musical Intimacy: Construction, Connection, and Engagement.

While the spectacle of the arena concert provides ‘favourite gig’ memories for many music fans, for others the small venue setting is vital to the intensity of the experience. Well-known small venues such as the Cavern, the Marquee and CBGB were key in many of the music careers and scenes that dominate popular music historical narratives. As ‘the testing grounds, the hangouts, the place to be’ small venues play a continuing role as performance spaces and networking sites for aspiring musicians, as well as contributing to the cultural economy by employing a wide range of workers frontstage and backstage and in promotion and merchandising. Often run as for-profit small businesses and ‘passion projects’, they walk a line between commerce and culture, existing in a state of financial precarity and, as brick and mortar spaces, are part of and influenced by the built environment and related policies, which are often detrimental. Although they sometimes tend towards niche participation and so can be problematic as social hubs (for example in relation to gender as discussed below), they play an essential role in the infrastructure and ecosystem of local music scenes and the live music industry more widely. In this chapter, Sam Whiting lays out the issues and tensions that are explored in greater depth in the book.

Explore further by reading Sam Whiting’s Introduction to Small Venues: Precarity, Vibrancy and Live Music.

The issue of sexual violence at live music events represents a flipside of the positives of intimacy in live music performance and the value of small music venues. In the context of gender inequality in the music industry and wider society, the live music environment is understood to enable sexual violence in a number of ways. Gender inequality and the gendered norms of certain music scenes lead to male dominance and the marginalization and sexualization of women. In small venues especially, where audiences are standing and often packed closely together, physical boundary norms are overturned, and standard behaviour that is part of some alternative music genres, such as participation in mosh pits, blurs the line between dancing and violence. With factors such as darkness, high volume levels, anonymity, and a lack of supervision thrown into the mix, as well as the normalization of high levels of alcohol and/or drug consumption, the risks are exacerbated further. Bianca Fileborn, Phillip Wadds and Ash Barnes argue that women’s experiences of live music concerts in many music scenes, including those that purport to be progressive, are commonly marred by sexual violence that is facilitated by social, cultural and environmental factors. The devaluation and dismissal of women’s experiences of sexual violence maintain the culture in which it persists, but activist groups such as UK-based Safe Gigs for Women are working to bring about change.

Explore further by reading Bianca Fileborn, Phillip Wadds and Ash Barnes’ chapter ‘Setting the Stage for Sexual Assault: The Dynamics of Gender, Culture, Space and Sexual Violence at Live Music Events’ in Towards Gender Equality in the Music Industry: Education, Practice and Strategies for Change.

Music festivals ‘used 7 million tons of fuel, generated 25,800 tons of waste and created a carbon footprint of 24,261 tons in the UK alone in 2018’. This stark fact highlights the tension between the growth of the live music industry, a cause for celebration from an economic and cultural perspective, and its environmental impact. The live music industry, especially large-scale festivals on green field sites, is beset with issues relating to energy, water, travel and waste. In relation to UK and EU legislation, the live music industry often leads the way in implementing strategies for positive change, such as initiatives to eliminate single use plastics and reduce food waste, and so-called ‘green riders’ (such as recycling, energy efficiency and carbon offsetting rather than a ban on brown M&Ms). However, while live music industry organisations such as Live Nation are aiming for zero carbon emissions by 2050, infrastructure is lacking to support this, for example in relation to plastic waste recycling. Although the economic effects of Covid-19 on the live music industry were devastating, the shutdown was purely positive for the environment, with waste, emissions and ecological damage dropping to zero. As Teresa Moore argues, ‘No one wants to see an end to live music’, but alignment between legislation and the music festival industry needs to be stronger to bring about change. This chapter highlights what is arguably the most pressing and timely of all the challenges faced by the industry.

Explore further by reading Teresa Moore’s chapter ‘Greening the live music industry’ in The Present and Future of Music Law.

Since the dawn of electronic music in the 20th century, music has been created out of, and responded to, the digital technologies of the era. But the emergence of new AI technologies poses greater questions and problems to artists as the ability to produce AI-generated music in a matter of minutes becomes a reality. What does the future look like for musicians and the industry alike in the face of AI developments? How have artists responded to these technologies? From virtual animation software to AI-generated EDM, from singing and dancing holograms to computer-created mashups, we've curated four chapters examining this relationship with an eye to what the future holds.

In the wake of new digital technologies, artists are able to explore different ways of representing a world where the virtual is becoming an increasingly unavoidable part of reality. Steen Ledet Christiansen, in his chapter from Cybermedia: Explorations in Science, Sound, and Vision, explores the significance of Radiohead using the MASSIVE animation software to create the music video for their single ‘Go to Sleep,’ the same technology used to generate the large-scale battle scenes of Lord of the Rings. Through this example, Christiansen examines how artists in the 21st century have adopted digital technologies as a crucial and core part of understanding the world around us, as well as a way to express the growing importance of the digital in our lives.

➜ To learn more, read Steen Ledet Christiansen’s chapter “A MASSIVE Swirl of Pixels: Radiohead’s “Go to Sleep”” from Cybermedia: Explorations in Science, Sound, and Vision.

Throughout its history, electronic dance music (EDM) has always involved collaboration between human and machine, the biological and the nonbiological. However, developments in AI technologies have blurred the boundaries between these defined roles as we enter an era of generative AI that can itself create music. Andrew Fry argues that these developments may soon (or may already) compel the machine to become the artist, breaking free from the limitations of biology, while the human becomes the tool, supporting the machine artist in their creative endeavours. To explore this as a possibility, Fry takes as his example the role of AI within EDM, specifically outlining the dynamic between the biological and the nonbiological.

➜To learn more, read Andrew Fry’s chapter “EDM, Meet AI: Cognitive Tools and (Non)biological Artists in Electronic Dance Music” from The Evolution of Electronic Dance Music.

Can digital technology prolong the artist’s life, even after death? The surge of interest in hologram concert performances by deceased artists has pushed the limits of this question, with famous performances by Tupac Shakur, Michael Jackson, and Roy Orbison all trading heavily upon notions of nostalgia, heritage, and the mythology of the deceased performers. These performances are often estimated to have cost multiple millions of dollars, even for as little as a four-minute performance. In Alan Hughes’ chapter from The Future of Live Music, he explores the commercial success of these tours, the increased sophistication of hologram technology used, and addresses the future of live music through the medium of stage hologram performances.

➜To learn more, read Alan Hughes’ chapter “‘Death is No Longer a Dealbreaker’: The Hologram Performer in Live Music” from The Future of Live Music.

The recent rise in popularity and sophistication of generative AI has many musicians wondering: how long until these computer algorithms replace humans in the creation of new music? Will tomorrow’s musicians be competing with robots for the top of the Billboard charts? Although AI tools to create entirely original music currently exist (and have existed for more than half a century), the general rise in popularity of AI has recently brought this concept to the forefront of the public mind. In their chapter from Remediating Sound: Repeatable Culture, YouTube and Music, authors Christine Boone and Brian Drawert explore the concept of AI-created art with regards to a single genre of music: mashups. A mashup is a new song created by blending two or more pre-recorded songs, a process that can be easily replicated by generative AI systems. In the process, Boone and Drawert provide an examination of the current state of AI-created music at its most rudimentary, and predict what this could mean for the future of music creation.

➜To learn more, read Christine Boone and Brian Drawert’s chapter “‘Technology Allows More People to do Things’: Artificial Intelligence, Mashups and Online Musical Creativity” from Remediating Sound: Repeatable Culture, YouTube and Music

Homepage image credit: A holographic image of Michael Jackson performs onstage (Kevin Winter/Billboard Awards 2014 / Getty Images)

What is Asian American music? We tend to try to categorize music into genres and styles, periods and places. But given that Asian American contributions to music bridge these qualifiers, this is an impossible question to answer. The Asian American movement of the 1960s and 1970s helped to create solidarity for Asian Americans across ethnicities, but the histories of Asian Americans and Asian American musicians are wide-ranging and diverse. From Japanese Breakfast to Mitski and from Karen O to Bruno Mars, we see the impact of Asian American musicians across musical spaces.

Rather than define Asian American music and sound, we can recognize the variety of musical contributions made by Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Native Hawaiians.

Often played at raves and nightclubs, and including subgenres ranging from house music to techno to dubstep, electronic dance music was a major part of the 1980s musical landscape, as it is still today. However, the EDM space has been predominately homogeneous and occupied by mostly white, middle-class participants. Raves and festival scenes are theoretically rooted in an acceptance of all, but the lack of diversity tells a different story.

Judy Soojin Park discusses the recent increase in young Asian American participants in the EDM space. The chapter focuses in particular on events organized by Insomniac Events in Los Angeles and the ways in which they have adopted the ideology of PLUR (Peace, Love, Unity, and Respect). Using interviews with young Asian Americans in the EDM community, this chapter discusses how Asian American “otherness” has not discouraged but rather motivated their involvement in EDM festivals. Through these interviews and analysis, the chapter explores themes of belonging and authenticity.

➜ To learn more, read Judy Soojin Park’s chapter “Searching for a Cultural Home: Asian American youth in the EDM Festival Scene” from Weekend Societies: Electronic Dance Music Events and Event-Cultures.

Japanese American writer Karen Tei Yamashita is known for exploring in her work themes of border crossing and migration. Her stories span Asia, Europe, and the UK, and draw from her personal history. Recipient of the National Book Foundation 2021 Medal for Distinguished Contributions to Literature, she is credited with helping to re-shape Asian American literature and literary studies.

Nathalie Aghoro’s chapter in The Acoustics of the Social Page and Screen explores Karen Tei Yamashita’s novel Tropic of Orange. A work of magical realism, the book assesses the connections of a diverse 1992 Los Angeles in the face of disaster — and the way sound and listening influences the trajectory of its characters. Aghoro analyzes Yamashita’s characters in the context of heterogeneity and social change, and highlights the impact of sound on socio-political boundaries.

➜ To learn more, read Nathalie Aghoro’s chapter “Sonic Sites of Subversion: Listening and the Politics of Place in Karen Tei Yamashita’s Tropic of Orange” in The Acoustics of the Social on Page and Screen.

Music of specific ethnic groups is often, and sometimes problematically, characterized by generalizations related to common practices and styles. However, to this effect, there is very little consensus on what Asian American music is or isn’t. Asian American musicians, like all musicians, create, influence, and are influenced by a huge range of contemporary styles.

Runchao Liu identifies a predominant thread in Asian American affect, however, as it relates to musical activism — tied to an unconventional nondominance. Liu argues that rather than being timid or weak, this style evokes an exceptional power. The essay uses the case studies of two Cambodian American musicians to demonstrate the potency related to this style of activism and its emotional honesty.

➜ To learn more, read Runchao Liu’s chapter “Unconventionally Confrontational: Radicalized Asian Affects, Diasporic Aesthetics and the Revival of Cambodian (American) Rock Music” in The Bloomsbury Handbook of Music and Art.

Native Hawaiian artist Israel Kamakawiwoʻole was best known for his signature ukulele sound and the medley “Somewhere Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World.” The well-known track was featured on his 1993 album, Facing Future, which would become the best-selling album of all time by a Hawaiian artist and was certified platinum in 2005. He received global recognition when his song, some years later, was used in commercials and movies. His legacy includes not only his music but his work utilizing his music towards the preservation of Hawaiian culture and rights.

Dan Kois discusses the history and lasting influence of this album. He explores Iz’s career, life, and challenges, and his journey to becoming a musical icon. He goes on to discuss the frequent licensing of the song, its impact on Hawaiian identity and society, and who profited from his music and why.

➜ To learn more, read chapter one, “Drive with Aloha,” and chapter two, “Local,” from Israel Kamakawiwo'ole's Facing Future by Dan Kois.

by Mads Krogh, Aarhus University Denmark

Within the past five years, broadcast corporations around the world have marked their centenary milestones. Radio, a key component of 20th-century mass-media modernity, has successfully transitioned into the digital age and continues to inform, entertain, and shape audiences. It sets the tone and cadence of intimate daily living while resonating in the broader realms of media, politics, and commerce.

With this collection of freely accessible chapters, we explore the significance of radio, especially for fostering communities. Special attention is given to music radio, a pivotal though sometimes underacknowledged aspect of what has propagated through the airwaves.

Radio is the medium of nation building par excellence. For the national broadcasting corporations established from the 1920s onwards, this was a main task. Radio provided a new means of addressing the nation, communicating to the public in real time, ‘as one’. Still, the task of creating and maintaining a sense of national identity proved challenging, for example, in the face of geographical or sociocultural distance and against local or transnational operators. This is demonstrated by J. Mark Percival in his exploration of the relation between music radio, space and place. Looking at the development of public service radio in Canada and Britain, he notes how superimposing a sense of a coherent national scene – an imaginary ‘national-place’ – over the potentially vast and disparate space of the nation-state is how political stakeholders gave radio a role in nation-building. Moreover, fending off external threats to the imagined national community has involved the delicate balance of incorporating strategies from transnational, e.g. commercial, operators into the national broadcasting corporation. Certainly, this disbands any simple notion of broadcasting (to) the nation.

Explore further by reading J. Mark Percival’s chapter ‘Music radio’ in The Bloomsbury Handbook of Popular Music, Space and Place.

The spread of radio from the 1930s as a household item coincides with the rise of middle-class tastes or, more precisely, it initiates a development, where ‘middlebrow’ gradually comes to signify a taste of its own (as opposed to being merely that which is neither high- nor low-brow). This is argued by Morten Michelsen, who details the multiplicity of musical genres scheduled by European operators in the 1930s, while noting that light music, parlor music, and modern dance music came to be ‘the bread and butter’ of music radio programming. This dominance of the airwaves by genres appealing to middle-class audiences contrasted with the official preoccupation by radio corporations with art music; that is, the promotion of highbrow tastes which offered a central means of legitimization in a time where education was considered the raison d’etre of public service radio. The juxtaposition and implied comparability of genres combined with the prominence of music representing middlebrow tastes nevertheless worked to showcase the latter as having a sense and significance of its own. To Michelsen, this marks the first phase in a history which encompasses other media institutional and musico-cultural developments (e.g. the 1960’s advent of rock criticism), while from the perspective of radio studies it provides a central case of radio’s potential for aggregating large-scale social communities based on class and taste.

Explore further by reading Morten Michelsen’s chapter ‘Being In-Between: Popular Music and Middlebrow Taste’ in The Bloomsbury Handbook of Popular Music and Social Class

In many countries, deregulation of frequencies and ideals about democratic and participatory media engagement have paved the way for community radio stations. Contrary to national broadcasting corporations and commercial networks, these often play a key role in voicing the concerns of local groups. In his chapter “Migrant radio, Community, and (New) Fado: The Case of Radio ALFA”, Pedro Moreira explores a station that is commercial, but which serves the Lusophone (i.e. Portuguese-speaking) community living in France, and specifically in a way that reflects the reality of this group. As such, Radio ALFA not merely represents the motherland to (and as imagined by) those living abroad but conveys instead a migrant Portuguese identity situated in the context of everyday contemporary France. The musical genre of (new) fado takes on particular significance in this regard. A genre of hybrid origin – mixing Afro-Brazilian and Portuguese inspirations – fado was picked up by the transnational music industries, circulated as world music and, thus, accorded a sense of cosmopolitanism. To Radio ALFA, promoting (new) fado offers a way of associating with this successful, traditional Portuguese yet contemporary and cosmopolitan cultural expression; that is, it offers a way for the station to articulate a sense of a vibrant and forceful migrant identity for the Lusophone community.

Explore further by reading Pedro Moreira’s chapter ‘Migrant Radio, Community, and (New) Fado: The Case of Radio ALFA’ in Music Radio: Building Communities, Mediating Genres

From the perspective of radio production, the appeal to different audiences is often thought about as a matter of formats – for example, talk radio, sports radio, contemporary hit radio, urban, or album-oriented rock. Formats streamline programming – i.e. the choice of music, news, style of presenters, sound of jingles, commercials etc. – according to the tastes of target audiences, whose attention is in turn sold to advertisers or mobilized to please political stakeholders. How such streamlining is achieved in the day-to-day workings of a radio station is a question that lends itself to detailed media ethnographic inquiry, as demonstrated by Katrine Wallevik. In her account of ‘Godmorgen P3’, a breakfast program aired by the Danish Broadcasting Corporation, she unravels the multiplicity of (f)actors engaged in program production. A host of human ‘accomplices’ take up different roles: researching, planning, playlisting and presenting. They employ a wide range of tools and technologies, thus enacting a complex human-non-human network. This constitutes a working culture but also a milieu of matter and meaning. Pursuing transactions in this milieu, such as the implication by programmers of scheduling software in producing musical flow, Wallevik unfolds a range of themes and, more fundamentally, onto-epistemological complexities in the apparatus that makes ‘Godmorgen P3’ cohere.

Explore further by reading Katrine Wallevik’s chapter ‘The Software’ in The Bloomsbury Handbook of the Anthropology of Sound

Whatever communities are assembled in or by radio, a basic question concerns the affective attachment or emotional investment that causes people to engage with the medium. What constitutes the love or at least affection for radio? In her book Radiophilia, Carolyn Birdsall provides a nuanced answer to this question, suggesting that loving should be understood as a site of action and practice – a site that transcends the listener’s individual relationship to the medium or to specific radio programs or stations, while encompassing instead a range of group practices and social moods. She lists a broad range of radio’s attractions, from its technological media qualities and types of content to the social uses developed by audiences, all of which afford diverse listener engagements. The concept of affect lends itself to thinking about both the emotional intensity and more-than-individual (i.e. agentially dispersed) character of engagements. Moreover, advocating the concept of affective practice, Birdsall stresses the way affects are to some extent cultivated in embodied, habitual and, again, social ways. This leads her to identify and – in the course of the book – explore a broader range of practices (knowing, saving, sharing), which associate and articulate the love of radio.

Explore further by reading Carolyn Birdsall’s chapter ‘Loving’ in Radiophilia

How are sound and space linked? How do they work together?

This content is available in our Sound Studies collection.

How does the space in which music is played recontextualise that music, changing the way it is interpreted and received by audiences? In the latter half of the 20th century, artist Max Neuhaus introduced the concept of the ‘sound installation,’ a musical endeavour in which sounds are “placed in space rather than time.” By transforming the environment in which music and sound is performed into an intentional, curated facet of the experience, these performances acquire a new spatial dimension to be grappled with. Jordan Lacey’s chapter from The Bloomsbury Handbook of Sonic Methodologies explores the questions brought forward by this spatial form of music, and the ways in which installations can be used as an artistic tool in the future of music and sound.

Read Jordan Lacey's chapter, 'Sound Installations for the Production of Atmosphere as a Limited Field of Sounds' from The Bloomsbury Handbook of Sonic Methodologies to find out more.

Until the dawn of the 1900s, music was a transient and ephemeral event; it disappeared when it was finished, and existed only with a specific framework of time. With the development of recording techniques, however, all this changed. According to legendary electronic composer Brian Eno in his chapter from Audio Culture: Readings in Modern Music, recording takes music out of the time dimension and places it in the dimension of space. It transforms what was once fleeting into something that is repeatable, enabling you to listen again and again to a performance in a way that is detached from the confines of the past, existing in a space that is always now.

Check out Eno's chapter, 'The Studio as a Compositional Tool', to learn more.

How does being in a specific place change our relationship with the music that we hear? How do space and time unfold together in our auditory imagination? And how does our experience of sound and space change when listening to music or sound art where field recordings, the sounds of everyday life, are incorporated within the piece? In her book Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art, Salomé Voegelin undertakes a philosophical study of time and space to grapple with these complex questions of how we experience sound.

Click here to read more from Salomé Voegelin’s chapter 'Time and Space'.

Acoustic design, the architectural pursuit of shaping the movements of sound through space to either minimise noise or harness the specific characteristics of that sound, provides a physical and practical basis upon which to study the relationship between space and sound. Perhaps among the most obvious examples we might think of are the soundproofed room or the concert hall; spaces designed to address an existing or anticipated sound event, albeit in opposite ways. But what about less obvious examples, spaces where sound and music are present, but not as the main event? In one chapter from Brandon LaBelle’s book Acoustic Territories: Sound Culture and Everyday Life, the author turns his attention to the shopping mall. Labelle delves into the “ambient architecture” of the shopping mall, exploring the ways in which it uses music and sound to construct an environment that serves its greater purpose, that of consumerism.

Click here to read more from Brandon LaBelle’s chapter ‘Shopping Mall: Muzak, Mishearing, and the Productive Volatility of Feedback'.

You know their songs, their voices; you see them on TV and hear them on the radio. But what does it really mean to be a celebrity, what kind of role do they play in shaping society and culture as we know it today? From the significance of the Eurovision Song Contest in political policy to the complicated nature of ‘celebrity feminism,’ from the legacy of dead celebrities to the addiction narratives of global rock stars – we’ve curated five star-studded chapters delving into how the idea of the celebrity plays a pivotal role in influencing the music and culture of our times.

You can also explore a range of other topics, artists, and countries previously in focus on the Bloomsbury Music and Sound platform on our featured content archive page.

Music has always held a mirror to the world from which it emerges. Socio-political anxieties find themselves voiced in the form of song, and these songs in turn can have a drastic and very real impact on large-scale political issues. The role of the musical celebrity, then, is often deeply bound to questions of cultural climate and political policy.

In Postwar Europe and the Eurovision Song Contest, Dean Vuletic explores this idea in light of how the Eurovision Song Contest has reflected and become intertwined with the history of postwar Europe from a political perspective. Eurovision is, he argues, ‘Europe’s biggest election,’ providing a platform upon which battles between capitalists and communists, Europeanists and Eurosceptics, reactionaries and revolutionaries have been played out – with musical performers being front and centre of these ideological battles.

Read Vuletic’s chapter ‘The Values of Eurovision,’ examining the role of Eurovision in shaping European political policy and cultural values.

The music from the swing era of the 1930s and 1940s laid the foundations for musical stardom as we know it today. Performers such as Louis Armstrong, Benny Goodman, and Duke Ellington experienced immense success throughout the entertainment industry, each becoming household names in a way that is comparable to that of today’s stars, and firmly cementing the idea of the celebrity in popular culture.

With the rise of the electro swing genre – a contemporary form of dance music built around samples from the swing era – one might expect this emphasis on celebrity status to have translated across to the emerging artists utilising the music of these original performers. And yet, as Chris Inglis argues in his chapter from The Evolution of Electronic Dance Music, this is not the case at all. Instead, when a remix of the likes of Armstrong, Goodman, or Ellington is heard, it is these artists who are invoked in the mind of the listener rather than the musician who has repurposed their work. As a result, the original stars of the swing era are in many ways enjoying a form of ‘second-hand stardom,’ reaching into the future to overshadow the acclaim that may otherwise be enjoyed by the adapter of their music.

Read Inglis’ chapter ‘Second-hand Stardom: Connotations of Sampling for Electro Swing’ to discover more about the complexity of celebrity status in the electro swing genre, as well as the broader implications of what this means for notions of celebrity in the 21st century.

How do female artists in the music industry engage with, promote, or complicate feminist ideas? Is the idea of ‘celebrity feminism’ – the way in which feminism is appropriated and endorsed by celebrities – inherently negative? Or do celebrity ambassadors for gender equality ultimately benefit the cause more than they harm it?

These questions delving into the complex relationship between feminism and celebrity are explored throughout Kirsty Fairclough’s chapter ‘Soundtrack Self: FKA Twigs, Music Video, and Celebrity Feminism’ from Music/Video: Histories, Aesthetics, Media. Through detailed analysis of FKA Twigs’ self-directed music video for her 2014 single ‘Pendulum,’ Fairclough provides a fresh perspective on the ways in which female artists are able to visually represent their own identities in audiovisual cultures, and at the same time grapples with the contradictions and pitfalls of ‘celebrity feminism.’

Read Fairclough’s chapter ‘Soundtrack Self: FKA Twigs, Music Video, and Celebrity Feminism’ to discover more.

The death of a celebrity is always tied to notions of legacy. Though the individual themselves has passed, the ‘idea’ of the celebrity – their work, the circumstances of their life and death, the things they stood for in the public eye – these things live on. And celebrities of large enough fame and stature are often elevated to a kind of mythic status, such as in the case of Elvis, Freddie Mercury, or Janis Joplin.

This process of posthumous celebrity myth-making reveals a great deal about Western conceptions of the celebrity both in life and death, particularly with regards to the stars of the music industry. In Christopher Partridge’s chapter ‘Transfiguration, Devotion and Immortality’ from his book Mortality and Music: Popular Music and the Awareness of Death, the author explores this idea in light of notions of religious transfiguration and idolatry. Much like how the figure of Jesus Christ can be separated into both the Christ of faith and the Jesus of history, so too, the author argues, is the figure of dead Elvis in popular culture a different being than the Elvis of historical fact.

Read Partridge’s chapter on ‘Transfiguration, Devotion and Immortality’ to discover more about the ways in which the legacy of musical celebrities continue to haunt and shape popular culture from beyond the grave.

Drug abuse and addiction have come to be seen by many as par for the course of a rock ‘n’ roll celebrity lifestyle. The dramatic trajectory of excess to illness, of relapse to recovery, is a narrative firmly situated in the public’s perception of rock stars. It is no surprise, then, to see the rise of ‘rock ‘n’ recovery’ autobiographies detailing this journey from the perspectives of stars such as Eric Clapton, Marianne Faithfull, and Anthony Kiedis.

But, given the complicated location of addiction within disability studies, how do these ‘rock ‘n’ recovery’ narratives engage with and elucidate notions of disability and celebrity? Where do they sit among the wider body of disability narratives? In Oliver Lovesey’s chapter ‘Disenabling Fame: Rock ‘n’ Recovery Autobiographies and Disability Narrative’ from Popular Music Autobiography, the author argues that these narratives form a distinct subgenre within disability studies; one that grapples with both altruistic and self-serving motives lying behind their creation, their hybrid genre, their construction of self, and – above all – their highly ambivalent relationship to fame.

Read Lovesey’s chapter ‘Disenabling Fame: Rock ‘n’ Recovery Autobiographies and Disability Narrative’ to learn more about the relationship between conceptions of disability and celebrity in the rock ‘n’ roll autobiography.

The relationship between music and philosophy is a close and interconnected one. Music can be used as a way of expressing and comprehending complex philosophical concepts, whilst the work of philosophers throughout history can further our understanding of music and sound – how it works, how we experience it. From the theories of Žižek to those of Deleuze, from silence to noise, from the Chinese philosophy of Qi to that of Pearl Jam – we’ve curated six chapters examining this fascinating dynamic between music and philosophy.

After Sound considers contemporary art practices that reconceive music beyond the limitations of sound. Music and sound are, in G Douglas Barrett’s account, different things. While musicology and sound art theory alike typically equate music with pure instrumental sound, Barrett sees music as an expanded field of artistic practice encompassing a range of different media and symbolic relationships. In light of this, the works discussed in the chapter “IDEAS MATTER”: Žižek Sings Pussy Riot use performance, text scores, musical automata, video, social practice, and installation in order to articulate a new and radical form of musical practice. Coining the term “critical music,” Barrett examines a diverse collection of art projects which intervene into specific political and philosophical conflicts by exploring music’s unique historical forms.

Read G Douglas Barrett’s chapter “IDEAS MATTER”: Žižek Sings Pussy Riot, which interprets the radical conceptual music of Pussy Riot through the lens of Slavoj Žižek’s philosophical work on the materiality of the violent threat.

How can the philosophical work of Gilles Deleuze help us cultivate a greater understanding of music? Does his work, where rigorously applied, have the potential to cut through much of the intellectual sedimentation that has settled in the field of music studies? Deleuze is a vigorous critic of the Western intellectual tradition, calling for what he calls a ‘philosophy of difference’. For Deleuze, ‘difference’ is not just a distinguishing factor between two things that are not the same, but a condition or state of being in which a subject makes itself distinct from all else. He is convinced that Western philosophy fails to truly grasp (or think) through difference, and as a result longstanding methods of conceptualizing music are vulnerable to this radical Deleuzian critique. But, as Deleuze himself stresses, more important than merely critiquing established paradigms is developing ways to overcome them, and by using Deleuze's own concepts this collection aims to explore that possibility in the field of music.

Read Sean Higgins’ chapter ‘A Deleuzian Noise/Excavating the Body of Abstract Sound’ on the conceptualisation of noise.

Marking the first discussion of the band in a scholarly context, Pearl Jam and Philosophy examines both the songs (music and lyrics) and the activities (live performances, political commitments) of one of the most celebrated and charismatic rock bands of the last 30 years. The book investigates the philosophical aspects of their music at various levels: existential, spiritual, ethical, political, metaphysical and aesthetic. This philosophical interpretation is also dependent on the application of textual and poetic analysis, with this interdisciplinary volume of work putting philosophical aspects of the band’s lyrics in close dialogue with 19th- and 20th-century European and American poetry. Through this philosophical lens, the writers explore the band’s immense popularity and commercial success, their deeply loyal fan base and genuine sense of community surrounding their music, and the pivotal place the band holds within popular music and contemporary culture.

Read Jacqueline Moulton’s chapter ‘Pearl Jam’s Ghosts: The Ethical Claim Made From the Exile Space(s) of Homelessness and War – An Aesthetic Response-Ability’

From the late 1990s until today, China’s sound practice has been developing in an increasingly globalized socio-political-aesthetic milieu, receiving attention and investment from the art world, music industry and cultural institutions. Nevertheless, its unique acoustic philosophy has remained silent. Half Sound, Half Philosophy: Aesthetics, Politics, and History of China’s Sound Art by Jing Wang traces the history of sound practice from the Chinese visual art of the 1980s to the widely-critiqued electronic music of the 1950s, to the fever of electronic instrument building in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as well as to the origins of both academic and non-academic electronic and experimental music activities.

This expansive tracing of sound in the arts resonates with another of the author’s goals: to understand sound and its artistic practice through notions informed by Chinese qi-cosmology and qi-philosophy. This involves notions of resonance, shanshui (mountains-waters), uanghu (elusiveness and evasiveness), as well as distributed monumentality and anti-monumentality. By turning back to deep history to learn about the meaning and function of sound and listening in ancient China, Jing Wang offers a refreshing understanding of the British sinologist Joseph Needham’s statement that “Chinese acoustics is acoustics of qi,” and expands upon the existing conceptualisation of sound art and contemporary music at large.

Read Jing Wang’s chapter ‘Sound, Resonance, the Philosophy of Qi’ which recontextualises sound studies in a worldview that emphasises correctionality, resonance, process, and transformation.

Listening to Noise and Silence engages with the emerging practice of sound art and the concurrent development of a discourse and theory of sound. In this original and challenging work, Salomé Voegelin immerses the reader in concepts of listening to sound artwork and the everyday acoustic environment, establishing an aesthetics and philosophy of sound and promoting the notion of a ‘sonic sensibility’.

A multitude of sound works are discussed by lesser known contemporary artists and composers (for example Curgenven, Gasson and Federer), historical figures in the field (Artaud, Feldman and Cage), and that of contemporary canonical artists such as Janet Cardiff, Bill Fontana, Bernard Parmegiani, and Merzbow.

Informed by the ideas of Adorno, Merleau-Ponty and others, Salomé Voegelin aims to come to a critique of sound art from its soundings rather than in relation to abstracted themes and pre-existing categories. Listening to Noise and Silence broadens the discussion surrounding sound art and opens up the field for others to follow.

Read Voeglin’s chapter on listening to ‘Silence’

Noise permeates our highly mediated and globalised cultures. Noise as art, music, cultural or digital practice is a way of intervening so that it can be harnessed for an aesthetic expression not caught within mainstream styles or distribution.

Reverberations: The philosophy, aesthetics and politics of noise examines the concept and practices of noise, treating noise not merely as a sonic phenomenon but as an essential component of all communication and information systems. This wide-ranging book opens with ideas of what noise is, works through ideas of how noise works in contemporary media, and then concludes by showing potential within noise for a continuing cultural renovation through experimentation. Considered in this way, noise is seen as an essential yet often-excluded element of contemporary culture that demands a rigorous engagement. Reverberations brings together a range of perspectives, case studies, critiques and suggestions as to how noise can mobilize thought and cultural activity through a heightening of critical creativity. Written by a strong, international line-up of scholars and artists, Reverberations looks to energize this field of study and initiate debates for years to come.

Read Scott Wilson’s chapter ‘Amusia, noise, and the drive: towards a theory of the audio unconscious’

To celebrate the publication of our new Black, African, and Afro-diasporic Music and Sound subject guide, we’ve assembled chapters from this still-growing subject area within our Music & Sound Studies scholarship. From soul to rap, Los Angeles to Nigeria, Black musicians, artists, and performers develop innovative approaches to music and sound. Our authors study the impact and intersections of diaspora and racism – as well as gender and sexuality – with the music and sonic innovations created by Black artists.

The ArchAndroid, Janelle Monáe’s first full-length album, takes place in the 28th century, in a city called Metropolis. In the album, Monáe casts themself as an android named Cindi Mayweather. In this hopeful, escapist, sci-fi album, the artist explores themes of liberation, love, and justice. Within Cindi Mayweather’s navigation of the dystopian Metropolis is an analogy for Monáe’s own determination of their life’s meaning. Just as they succeed at finding love, challenging unjust hegemony, and fulfilling their destiny in the fictional world of the album, Monáe reclaims the American Dream for themself, in their multiplicity as a Black, queer nonbinary person.

Read our 33 1/3 volume on The ArchAndroid

This chapter is about sonic art that faces the dark depths of history and its violence against Black and Indigenous peoples. The author highlights several art works, focusing on the grand scale of these works and their refusal to be reductive or clichéd. The scale is notable because until recently, most sonic experiences were not solitary. Which is to say, most of what could be heard, listened to, was not done privately or by one person. Contrast this to the daily experience or potential to listen to music, podcasts, books, or any kind of sound through headphones or other technological innovations. Featured works include the installation The Battle of Little Big Horn by Senegalese sculptor Ousmane Huchard Sow. Its acoustic production is the audible resistance by Indigenous Americans to the theft of their land and the violence of settler colonialism. Jacques Coursil’s Trails of Tears is a compact disc album. Coursil does not use any stereotyped African sounds (such as drum beats or call and response) but rather employs “abstract, variable, insistently modern” music, with “three distinctive musical textures and styles of improvisation across the album, with three very different ensembles, it withholds any smoothing gestures or supposed coherence between sections.”

Read Tsitsi Jaji's chapter "Unsettled Scores: Listening to Black Oklahoma on the American 'Frontier'" from The Acoustics of the Social on Page and Screen edited by Nathalie Aghoro

Opening his book with a reflection on learning to DJ as a teenager, the author explains his crew member’s theory the Law of Seven. This theory required a “manual rewinding of a vinyl record counter-clockwise seven times to bring the record back to its beginning.” DJing is a nuanced art. While there is an evident physical relationship between the A side and B side of a record, “while the sonic relationship is not always immediately perceivable.” When a DJ plays a record, they have the opportunity to create their own meaning and relations from one track to the next. Campbell explores this sonic artistry that stems from DJing and other music and sound playing techniques. Through theory such as Alexander Weheliye’s sound thinking and with examples including Jamaican sound systems, Negro Spirituals, and Samba, this book analyzes and critiques sonic architecture and innovation in the African diaspora.

Read Mark Campbell's introductory chapter to Afrosonic Life

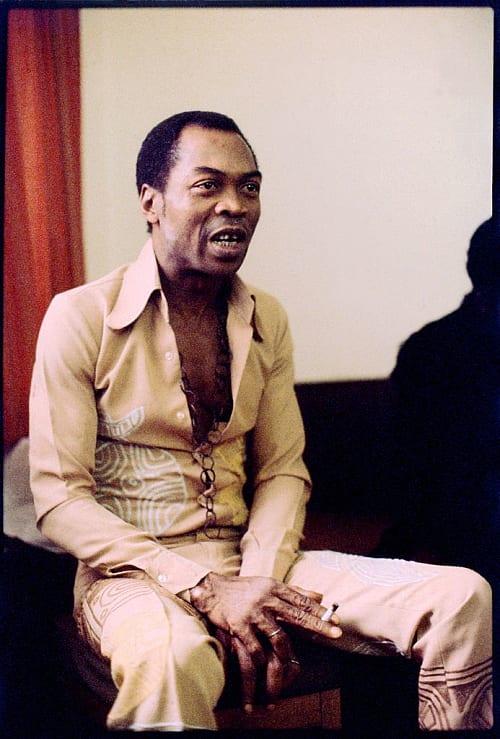

A young Fela Kuti, the prolific Nigerian musician and artist, grew up in the newly independent, newly formed Nigeria. He was exposed to politics at home from an early age, as his mother was involved with the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC). Years later, Fela Kuti started his career as a man without much attention to politics. The apolitical Fela Kuti recorded “Viva Nigeria,” a pro-government song, in 1969 which, if discovered and supported by the Nigerian government, could have propelled Kuti to greater power and fame.

By 1970, as Fela Kuti returned to Nigeria from the United States and Nigerians faced harsh economic realities and inequality due to the “oil curse,” the end of the civil war, and government policies, he developed new ideological sensibilities. These beliefs were channeled through Afrobeats music, a departure in genre from his earlier style, including tracks “Buy Africa,” “Black Man’s Cry,” “Why Black Man Dey Suffer,” and “Beggar’s Lament” (all 1971), and Fela Kuti became a political musician.

He initially faced resistance from his audience, not accustomed to his political tone, and the government acutely rejected his political messages for many years. Kuti was unjustly arrested by government forces in 1974, and in 1978 those same forces torched his home and attacked his 77-year-old mother. He never quite recovered from these tragic events, but he was resolute in his beliefs. Throughout his career, Fela Kuti has remained committed to speaking against injustice and inequality through Afrobeats.

Read Adeshina Afolayan and Toyin Falola's chapter, "Fela and Postcolonial Political Economy of Nigeria"

As of this moment, Kendrick Lamar is one of the most famous and celebrated rappers. He’s won a Pulitzer Prize and performed at the Super Bowl Halftime Show. Everybody knows Kendrick; he’s made it as far as any artist could go. But what does it mean for this celebrated rapper to be seen, to be heard, but to continue to experience the violence and loss he’s elucidated in his lyrics? In a brand new 33 1/3 title to Bloomsbury Music & Sound, author Sequoia Maner artfully examines Kendrick Lamar’s portrayal of the commodification and exploitation of black expression in To Pimp a Butterfly. The album is a blazing critique against the fetishization of Black art which simultaneously allows record companies (and other brands) to profit from Black artists like Kendrick, while the social, political, and economic realities of America do not shift the material circumstances of the Black community at large.

“They want our rhythm, but not our blues.”

In the early 1970s, as much of American society had begun to transition into the feel-good euphoria ushered in by Disco, a different sound was swimming against the current. Searching for a creative outlet through which they could respond to social inequities, poverty, and political disenfranchisement, Black artists began to synthesise poetry, spoken word, improvisational rhythms, funk, soul, and jazz riffs. The resultant amalgamation was a syncopated orchestration of ancestral African chants and vocal riffs delivered over a contemporary soundtrack of quantized rhythm and groove. The content and substance of this new art form was uniquely Black American. It was hip hop.

However, by the mid-1980s, hip hop had started to lose its focus on Black nationalism in favor of more universally palatable, and therefore commercial, themes of excess and materialism. The Beastie Boys became the first successful white rap group. Their subject matter, partying and rebellion against parental control, allowed them to operate at a safe distance from racial, and therefore controversial, conversations. But this watering down of hip hop resulted in a commercial commodity more than a cultural vehicle.

Marcus Thomas traces the history of hip hop and its relationship with race in late twentieth and early twenty-first century America. Exploring the impact of artists from The Beastie Boys and Vanilla Ice to Eminem, he asks to what extent hip hop has been appropriated or adopted by white artists, record companies and audiences. Thomas considers whether Black artists and consumers will continue to accept white performers in traditionally Black spaces and whether Black artists will innovate away from hip hop.

Big hair, bright colors, leg warmers. Cold War, Thatcher, Reaganomics. There was a lot going on in the ’80s, and perhaps not all of it was for the best, but at least there was good music.

If you grew up thinking the ’80s were the opposite of cool, now’s the time to learn a few things about this iconic and influential era. Everything comes back, and in the case of ’80s music, the innovations of the era have never truly left. Or if you feel as if you’ve only just emerged from that decade, you’ll be delighted to find a wide range of scholarship on the artists, styles, and trends that defined it. From development in music technology that transformed and defined the decade’s sounds to artists who are still revered today, the 1980s were a foundational era for electronic music, hip-hop, and the independent record label and a transformational era for rock music and popular music.

As the ’70s gave way to the ’80s, New Wave became the new thing. Broadly encompassing varying elements of popular music, New Wave featured synthesizers and other electronic sounds and an overall lighter approach than the punk rock that preceded it. The ’70s had also been the era of glam rock, with musical acts like Roxy Music and David Bowie incorporating bold costuming in their hair, makeup, shoes, and clothing, such that the artists had strong visual signatures in addition to musical ones. What was simmering in the ’70s came to a frothy boil in the ’80s. In the first two years of the new decade, the New Romantics, a fashion movement originating in London nightclubs, came to the fore. The quirky, bold fashion of the New Romantics was a natural progression of the previous decade’s glam rockers. Bowie and Roxy Music inspired Japan, and Japan and Roxy Music inspired a young Duran Duran, and by the spring of 1982, Duran Duran had released ‘Rio’.

Why was ‘Rio’ so successful? In "Why Rio Matters" from Annie Zaleski’s Duran Duran’s Rio, the author explains that cinematic music videos (and the rise of MTV), a successful headliner tour, and an intangible coolness were all factors. Why was ‘Rio’ important? It ushered in the fresh, experimental sound of New Wave to an audience receptive to the fun, upbeat tracks. Duran Duran were certainly a product of their time. Other acts had laid the groundwork and Duran Duran carried the torch into the next era of rock music. ‘Rio’ went on to spend 129 weeks on the US Billboard album charts.

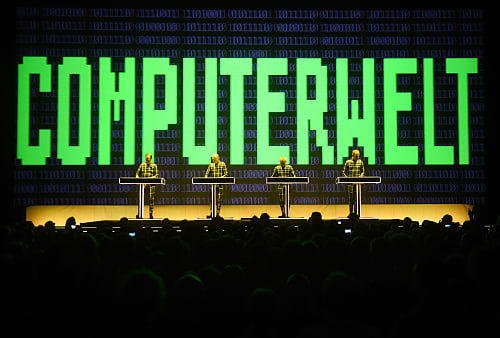

The 1980s saw a revolution in the form of electronic music. In her chapter in Modern Records, Maverick Methods, Samantha Bennett discusses the electronic instruments that featured largely in the music landscape: the LinnDrum Machine, the MIDI (which enabled multiple systems to connect), sequencers, and samplers. The synthesizer in particular may be the most distinctive electronic instrument of the era and one still crucial to music made today.

The synthesizer is an electronic instrument, typically operated through a keyboard, that creates a variety of sounds. Some artists, like Wendy Carlos, became well known for their mastering of the synthesizer. Importantly, samplers could be used in conjunction with synthesizers or sequencers, allowing the sampling for which rap is well known to flourish. Public Enemy’s ‘It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back’ (1988) and The Beastie Boys’ Dust Brothers-produced ‘Paul’s Boutique’ (1989) are two examples of records almost entirely constructed from samples.’ Introducing electronic music complicated music for the better, enabling intricate production and editing, as well as new sounds, rhythms, and instrumentations.

From 1979 to 1987, Hip-Hop largely remained authentic to its countercultural roots in challenges manifested in the urban landscape of the late twentieth century.

In 1982, ‘conscious’ rap music came into prominence when Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five released ‘The Message’ through Sugar Hill Records, co-owned by the innovative producer Sylvia Robinson. J.B. Peterson explains the term ‘conscious,’ as referring to an artist’s lyrical realization of the various social forces at play in the poor and working-class environments from which many rappers hail and from where the music and culture of Hip Hop originated. ‘The Message’ was a powerful response to, and commentary on, inner-city conditions in America. Since then, the subgenre of conscious rap music has continued to produce some of the most inspired songs for the enlightenment and uplift of Black and brown people including Run–D.M.C.’s ‘Proud to Be Black’; KRS-One’s ‘Self-Destruction,’ ‘Why Is That?’, and ‘Black Cop’; and Public Enemy’s ‘Can’t Truss It,’ ‘Shut ‘Em Down’, and ‘911 Is a Joke’.

From the late 1980s, rap and rappers began to take center stage as Hip-Hop exploded onto the mainstream platform of American popular culture. The extraordinary musical production and lyrical content of rap songs artistically eclipsed most of the other primary elements of the culture.

In their chapter from Popular Music in the Post Digital Age, authors Patryk Galuszka and Katarzyna M. Wyrzykowska define the broadly applied term ‘independent’ as it pertains to record labels and artists as those who distribute their records through distributors not affiliated with major record companies. Any artist who distributes through a major record label owes a portion of their profits to the label, but the power and connections of the label almost always ensure greater and more predictable sales.

The independent label first came about in the 1980s. To distribute music without ties to a major record label gave the impression of a group more in-tune with what audiences wanted, a group with better ethics and aesthetics, musician- and worker-centered, that eschewed the bureaucracy and corporatism of a major label. The challenge, of course, is to succeed in a capitalist environment as a small, ethically minded or ideologically pure, label. The 1980s saw the pinnacle of independent labels’ success, although many would-be indies were plagued by poor business management and a challenging landscape. By the 1990s, in order to succeed, the smaller, independent labels often found themselves absorbed by or in partnership with the major record labels. Today, record labels continue to experiment with different ways of distributing music, balancing costs, and maintaining the line between their ideals and the means to succeed.

It is arguably the most famous music video of all time. One that broke the mould of its format. It has been recreated, its choreography rehashed and repeated, countless times. Uploaded to YouTube in 2009, decades after its 1983 premiere, the official version has over 800 million views. It is, of course, Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller.’ At 14 minutes long, it is a short film and unlike any other music video of the time. There is a story within a story, complete with narrative arc, a cast of characters, and complex costuming. To this day, donning a red leather jacket and single white glove effectively recalls the image of Michael Jackson. Though he didn’t wear the single glove in this video, Jackson’s silhouette is distinctive and recognizable in slim pants that hit above the ankle, white socks, and understated black loafers. The costume is both fashion and function, allowing Jackson to dance with precision and to display his moves to their advantage. In other videos, Jackson made a white fedora and two-tone patent leather shoes iconic. But the ‘Thriller’ video is not iconic for its memorable outfits or choreography alone. In form and style, it was both innovative and risky, but Jackson pulled it off, where few would have tried and even fewer been successful.

In his chapter "Television Vaudeville" in Money for Nothing, Saul Austerlitz describes how ‘Thriller,’ emerging at the end of 1983, took the ambiguity at the heart of portrayals of Jackson and made them the centerpiece of what was then the largest, most expensive music video ever made. The fourteen-minute video starred Jackson in his own horror film, one that played up the confusion inherent in his persona. Was he a bland nice guy—boyfriend material? Or was there a threatening wacko lurking within? In raising these doubts, Jackson was toying with a nation of white record buyers and MTV watchers, simultaneously telling them not to fear him as a black man and raising doubts about his own trustworthiness.

Both Kate Bush and Madonna have a status that has been fairly rare for women in the popular music world. In the 1980s, Kate Bush opened the way for female performers who would not be limited by the gender constraints of rock or pop. In that same decade, Madonna redefined what it meant to be a pop star and, in the process, changed the appearance, sound, and intentionality of modern popular music.

In her chapter "Feminism, Gender and Popular Music" in The Bloomsbury Handbook of Feminism and Religion, Alison Stone discusses the game-changing success of Madonna and Bush as that of auteurs: artists who, while collaborating on their music with many other people, have exercised as much overall control over the process and its products as possible. The two artists have done this in different ways: Bush has retained control over songwriting, recording and production, while Madonna’s authorship has been more focussed in areas such as performance, image changes and promotion and constructing star personae, as well as her significant musical input.

Read Alison Stone's chapter, "Feminism, Gender and Popular Music", here.

In "The Female Voice" (Beyond and Before: Progressive Rock Across Time and Genre), Hegarty and Halliwell draw attention to Bush's video and dance realizations in the 1980s. She contributed centrally to the videos, creating detailed storyboards for singles such as ‘Army Dreamers’ (1980) and directing videos for singles taken from her later albums. ‘Wuthering Heights’ compresses Emily Brontë’s 1847 gothic novel into a five-minute dramatic ‘songscape’ in which Bush plays Catherine Earnshaw. When questioned on a BBC Nationwide special, Kate Bush on Tour (1980), about what she might do next after two albums and a successful tour, the twenty-one-year-old Bush responded, ‘I haven’t really begun yet. I’ve begun on one level, but that’s all gone now so you begin again.’

Over recent years, much attention has been paid to the topic of gender equality in the music industry and in the wider sphere of music and sound. To mark Women’s History Month, we explore how a selection of female artists and scholars have responded to some of the key challenges faced by women. These include re-examining music histories that focus on men, asserting musical identity and liberation, overcoming lack of access to male-dominated music spaces, and challenging the sexualization of a performance.

Much has been written about the Beatles and their predominantly young, female fan base. Author Christine Feldman-Barrett recognizes that a challenge in identifying as both a Beatles fan and a scholar is that her work can be dismissed as merely that of a fan, therefore diminishing her authority. The disregard of women’s contributions to the immense body of Beatles scholarship is consistent with a pattern of mocking or de-emphasizing the role of women in the general history of the Beatles.

However, from Astrid Kirchherr’s early photos of the band and Linda Eastman (later McCartney’s) documentation of their work, to the fans of all ages and eras whose passion for the Beatles helped sustain first their success and then their legacy, it’s clear that without the support of and legitimization from women and girls, the Beatles would not exist in the way with which we are familiar.

Learn more in the introduction to Christine Feldman-Barrett’s A Women’s History of the Beatles.

In the preface to Janet Jackson’s The Velvet Rope, author Ayanna Dozier notes that she refers to the artist as Janet throughout the book, so as to recognize her autonomy as a solo artist, distinct from her very famous family. On The Velvet Rope album, Janet celebrates her entire being and all of its possibilities. She celebrates her Blackness, her dignity, her feminism, her sexuality and desire, and her liberation.

Dozier asserts that in claiming what is hers, Janet sets an example to be followed; Janet deserves the self-actualization she channels through the album. Why wouldn’t she? Do we not all exist in multiplicities that should be recognized as distinct elements but, together, inextricable aspects of a single person? Shouldn’t we be allowed to exist wholly without fear of retribution? As a Black woman, Janet is made to navigate respectability politics and societal expectations of what she should or shouldn’t do, with implications for her character and career if she were not to comply. The listener of The Velvet Rope is witness to Janet’s liberation, and she should know that she deserves liberation, too.

For more on Janet Jacksons’ liberation, read this chapter from Ayanna Dozier’s Janet Jackson’s The Velvet Rope.

In Birmingham, UK, British-Asian rapper Hard Kaur found that success was not easy to come by in the male-dominated spaces of bhangra-influenced British Asian music or mainstream hip-hop. She forged her own path, recording a song for which she rapped in Hindi in a collaboration with British-Asian hip-hop group the Sona Family. This collaboration attracted attention from Bollywood music directors interested in a fresh voice, meaning Kaur was able to succeed by using multicultural, multilingual, and transnational strategies.

In her chapter from the book Towards Gender Equality in the Music Industry, Julia Szivak highlights that part of Kaur’s strategy for success is to project a tough demeanor and confrontational attitude, qualities more typically associated with masculinity. Does this mean that in order to succeed in a male-dominated industry, one must adopt the posture of the dominant culture? Would it have made a difference if she hadn’t? Do we make a distinction between women who are being tough to seem masculine and women who are tough and not trying to be masculine?

Explore further by reading Julia Szivak’s chapter from Towards Gender Equality in the Music Industry.

ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response) has enjoyed a bloom of popularity in mainstream social media in recent years, giving platforms to the mostly female ASMRtists who create sensory-driven audio-visual content. Such content is often described as inducing “tingles” and similar feel-good sensations. From a sonic perspective, ASMR generates interesting analyses of tools and materials that amplify its efficacy, like high-quality headphones or, counter to expectations, cheap fabric, as well as the intimacy and pleasure it creates for the listener.

In their chapter from The Bloomsbury Handbook of the Anthropology of Sound, Smith and Snider consider the impact of the sexualization of ASMR and the accusations that it is inherently fetishistic. Responses to ASMR content can be gendered in nature and sexuality projected onto the performer based on the listener’s interpretation of the content’s sound and set up. For example, whispering and prolonged eye contact with camera have been read as sexual, despite the performer’s non-sexual actions. The authors note that ASMR explicitly seeks to create intimate, caring, comforting, and nurturing experiences for their viewers - qualities typically associated with femininity and womanhood. This further exacerbates the gendered analyses of ASMR based on an individual’s physiological response. The sexualization of ASMR forces a closer examination of the boundaries between pleasure, intimacy and sex, and what they mean in a digital space.

For more on ASMR, read Naomi Smith and Anne-Marie Snider’s chapter from The Bloomsbury Handbook of the Anthropology of Sound.

Sound art is art. It is an art form that encapsulates all types of sonic expression—from acoustic, to digital, to sounds recorded in the natural world. Sound art is not an isolated art form; by its nature, it intersects with other artistic disciplines: visual art, dance, theatre, film, concept and installation art, and more.

The relationship of sound and music to the art world cannot be disregarded in the rise of sound art. The Futurist and Dada movements produced several theories about using noise in music, mechanized instrumentation, and spatialized sound; sound sculpture could be considered to a certain extent to be an offshoot of Kinetic art; and sound installation has an aesthetic kinship to Land art. In the twentieth century, there have been numerous examples of sound or music pieces made by visual artists. Following the departure from traditional painting and sculpture toward other forms of visual art and performance that began with Dadaism and Futurism, artists affiliated with Fluxus and early video and performance art in the 1960s also engaged with sound as another alternative medium. Most sound by visual artists is formulated and/or performed as music, although in Conceptual art sound becomes an element in installation works that seek to dismantle the accepted definitions of an art object.

For more on theories of sound art, read Alan Licht on “Sound and the Art World” in Sound Art Revisited.

Jung In Jung creates sound compositions by introducing interactive technology into dance choreography. In choreographing a contemporary dance piece, Jung simultaneously composes a sonic experience. Dancers are tethered to the cable of Gametrak controllers, which create sound when moved. The motion-tracking technology is used to investigate the aesthetic impact on spectators. Working in conversation with theories on movement put forth by luminaries in contemporary dance, including Merce Cunningham and William Forsythe, Jung incorporates sound technology, making for a collaborative audio-visual project that combines sound and choreography in the making of a composition.

For more on sound art in choreographic practices and contemporary dance, read Jung In Jung on “Sound – [object] – dance: A holistic approach to interdisciplinary composition” in Sound and Image: Aesthetics and Practices.

“Cinema is a multisensory form, through which sound is present again and again. Even in the persistently visual aspects, ‘sound often is [so] integral to the imagery’. Beyond its role in individual pieces, the sound is reflective of culture at large. Since cinema, as all other art, is an artifact of its time, the type of sounds / the nature of the audio in cinema is reflective of cultural norms, preferences, and trends.”

Cinema is not dependent on a single medium but is instead an art that exists as “intermedia,” a form that defies categorization. This is due, at least in part, to the overlap between media such as television, film, and radio, as well as books, magazines, and newspapers. In Paul Hegarty’s words, “the machine is not the medium.” In years to come, the technology used to create cinema (and the perspective of the creator) will change, trends will come and go, but cinema itself will exist. From ciné-romans to photo novels, soundtracks to scores, cinema will ever expand into new formats as filmmakers, artists, and storytellers push the art form in new directions and likely in the form of video art installation, the post-medium.

For more on cinema and sound, read Paul Hegarty on “Expanding Cinema” in Rumour and Radiation: Sound in Video Art.

“The sound art scene is not limited to the Northern hemisphere. Rather, it is globally distributed and has for decades also appeared in various manifestations and constellations in the Global South.”